Thorns and Flowers

"Your father was quite the charmer," said the lady in my dream. Her powdered face looked at least eight decades old, her dyed reddish hair was curly and short. She was a brassy sort, but good-natured, and she managed the building of the apartment into which, in my dream, I had wandered. It was a little flat in Brooklyn with yellow-hued walls and green tiles and shiny linoleum, a clean, uncluttered place, an apartment with good bones.

"Oh, vintage linoleum!" I said stupidly, and I was vaguely aware of having stepped into the best of the 1950s, an island chipped off the era of my childhood miraculously still afloat.

More important, I had discovered my father's secret refuge in the city, and even in his absence there was evidence of him: the graceful remnants of a hand-painted mural in a foyer, the gleaming floors, the tidiness...it made me so happy to know that there had been a place of retreat for him, a place where he could be himself, accountable to no one, unburdened and autonomous.

"It's still his," said the lady, "or yours, if you want it."

I wanted it. I did.

So it was what I call a good dream...a wish fulfilled retroactively, a sense of the presence of someone I loved. I guess the wish is that my father had had more happiness, a sweet hidden life apart from the struggles that I witnessed.

But isn't it curious the degree to which he still inhabits my head? It reminds me of a cartoon I read in the New Yorker last week, where a mother is tucking in her little boy and reassuring him: "The only ghosts you need fear are the ghosts of your past–which will gnaw away at your soul, riddle you with self-doubt, and ultimately sap you of your will to live."

That pretty much sums it up, although it hasn't sapped me yet of the will to live.

In fact, another telling aspect of the dream is how much I coveted that apartment for myself, a little getaway flat like my friend Cornelia has in Berlin, but in 1950s Brooklyn. How easily I can picture the neighborhood in summer rain, with everything I need nearby, and myself by a window and the warm-hued wall, leaning back easily into occasional solitudes that bear no resemblance to loneliness, feeling safe and certain of myself in a place that fits me like a nest.

Someone who goes with half a loaf of bread to a small place that fits like a nest around him,

someone who wants no more, who's not himself longed for by anyone else,

He is a letter to everyone. You open it.

It says, Live.

That's from Rumi (1207-1273), translated by John Moyne and Coleman Barks, and I don't exactly why, but this seemed the time to share it.

Maybe because last week I heard a catch in my sister's voice and understood that she dwells on the constant cusp of tears, and the catch was like a door unlatching, but I stepped back before it opened.

And I was with a friend when she crashed her bicycle, over the handlebars, onto the gravel like a crumpled flower, tumbling in an instant from fresh and carefree to bruised and askew, and remembered again how fragile we are. (She's okay, I guess, but very sore, and we're trying to glean the lessons.)

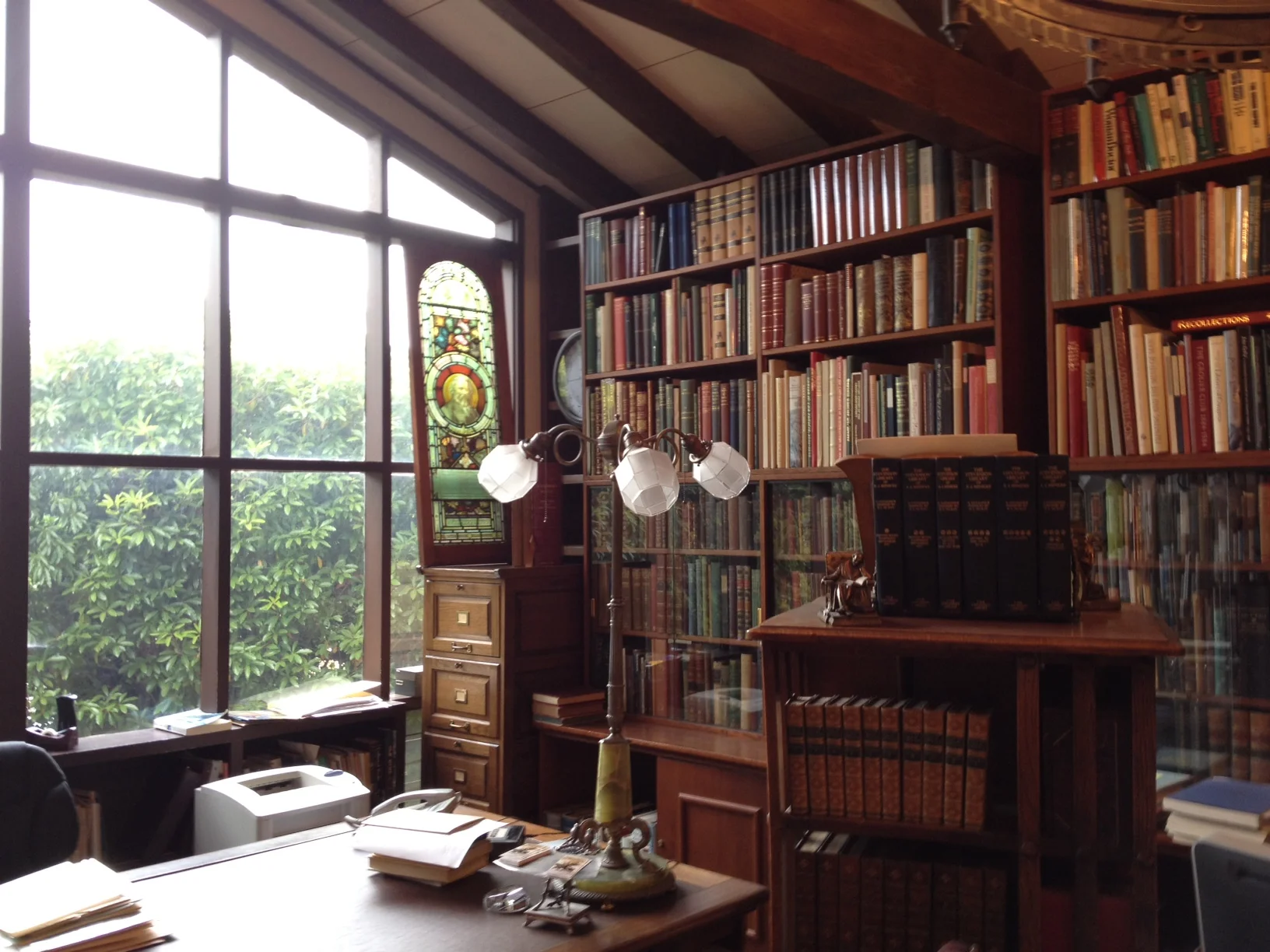

And I found a bookshop tucked away like a secret temple in an old Santa Barbara adobe, crammed with rare books and prints and antiquities, with an Oxford sort of ambiance, dark wood, a slant of light, the smell of aging pages.

There was that conversation with the Japanese man who chose to harvest kindness from his history. And there was an afternoon in the living room when Monte was listening to the nimble, husky guitar of Junior Brown and he suddenly said, "Let's waltz" and took my hand, and waltz we did.

So I'm looking up, climbing out of a dark place, refueling my light. My friend Dan recommended a book by Jack Kornfield, and when I googled it, I found this excerpt:

When Siddhartha sat by the river at the end of the story by Herman Hesse that many of us read in high school, he finally learned to listen. He realized that all the many voices in the river comprise the music of life: the good and evil, the pleasures and the sorrows, the grief and the laughter, the yearnings and the love. His spirit was no longer in contention with all of life. He found that along with the struggles was also an unshakable joy.

Rumi again:

Do not sit long with a sad friend.

When you go to a garden, do you look at thorns or flowers?

Spend more time with roses and jasmine.

The thorns will make themselves known. Remember roses, jasmine, or even a clumsy waltz.